Contrary to common practice in other countries, including in Southeast Asia, there are no private arms manufacturing companies in Myanmar: in its entirety, Myanmar’s weapon industry is a military-run affair.33 As a fully State-owned enterprise, the DDI34 is the principal organisation overseeing the domestic manufacture and assembly of weapons in Myanmar. The DDI has always remained under the firm control of the military, including during the years of coalition government with the National League for Democracy (NLD). As a part of the military’s structure, the DDI operates under the Myanmar Ministry of Defence and reports to the Office of the Commander in Chief.35 The current Chief of Defence Equipment Production at the DDI – responsible for weapon manufacturing at KaPaSa factories – is Lieutenant-General Kan Myint Than.36 Prior to assuming his function at the DDI, Kan Myint Than served as the Commander of Defence Services Science and Technological Research Centre (DSSTRC) in Pyin Oo Lwin, Mandalay Region.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Myanmar’s total defence spending budget amounted to 3.3% of the country’s gross domestic product in 2021.37 This figure is indicative only as it does not take into account the many ways in which the military supplements its income through off-budget sources.38 While SIPRI’s data does not indicate the share of the budget earmarked for in-country production of weapons, proposed defence spending budgets leaked from the MOD suggest that, in 2020, the military requested over 29.68 million USD for military vehicles manufacturing and 65.22 million USD to purchase machinery for “Defence materials factories.”39

KaPaSa Factories

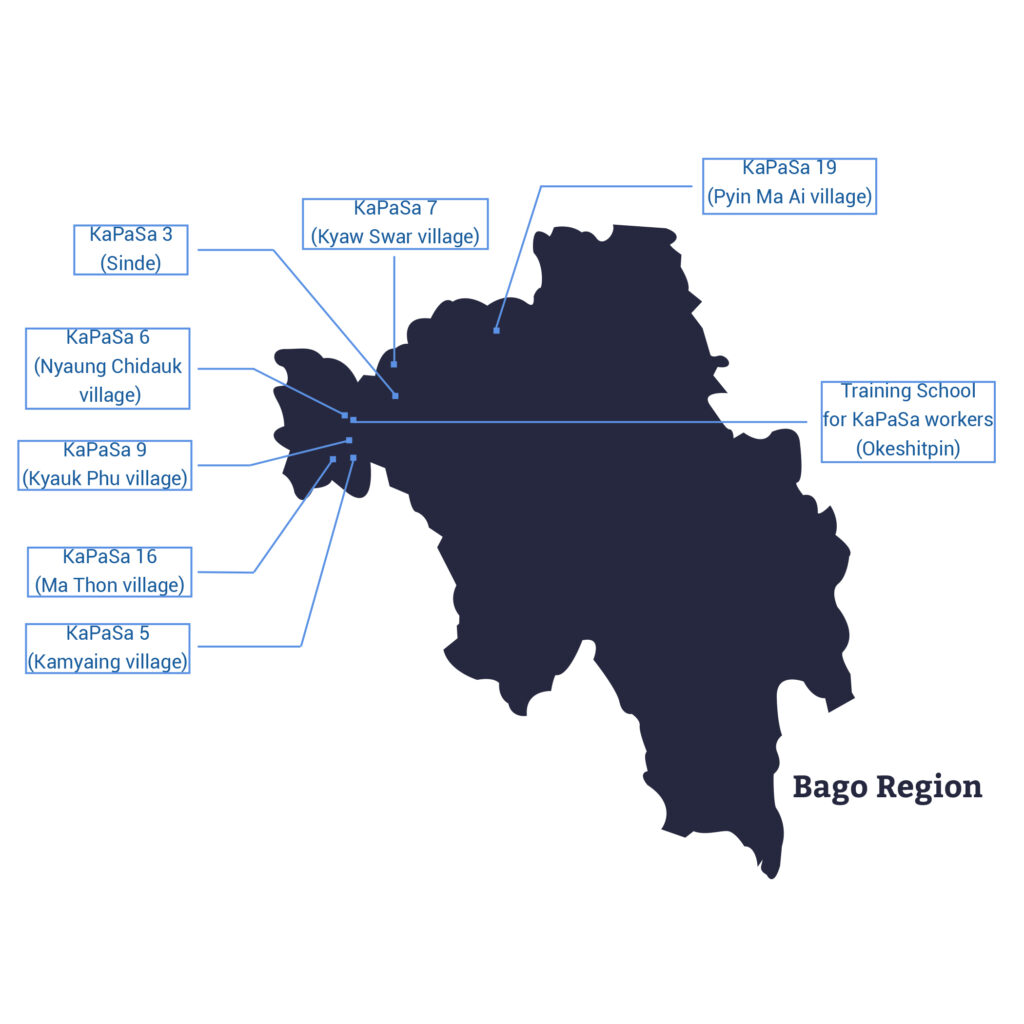

The Myanmar military’s arms production takes place at so-called “Defence industry” factories that are located in about a dozen different locations across the country. Commonly referred to as KaPaSa factories (after the Burmese name for the DDI, Karkweye Pyitsee Setyone), many of the factories were initially established in the 1950s with the technical support of West Germany and Italy. Since then, the factories have multiplied in number and their production lines have been diversified. While individual KaPaSa factories may initially each have run several different production lines simultaneously, they appear to have become increasingly specialised. In practical terms, this implies that, at present, some of the KaPaSa factories produce specific components for larger weapon systems that are assembled in other KaPaSa factories, or that KaPaSa factories produce a specific type of weapon in its entirety (typically a specific “generation” of a given weapon),40 or focus on manufacturing tool holders41 for CNC machines in use at other KaPaSa factories.42 Put differently, the KaPaSa factories perform a wide variety of functions, from processing raw materials and manufacturing components, to making arms and equipment, reassembling components shipped into Myanmar from abroad, adapting dual- use technologies43 – legally or illegally acquired from other countries – and performing major repair and maintenance functions. The result is a large, sprawling multi-layered and multi-faceted arms industrial complex that has evolved over the years and is still evolving.

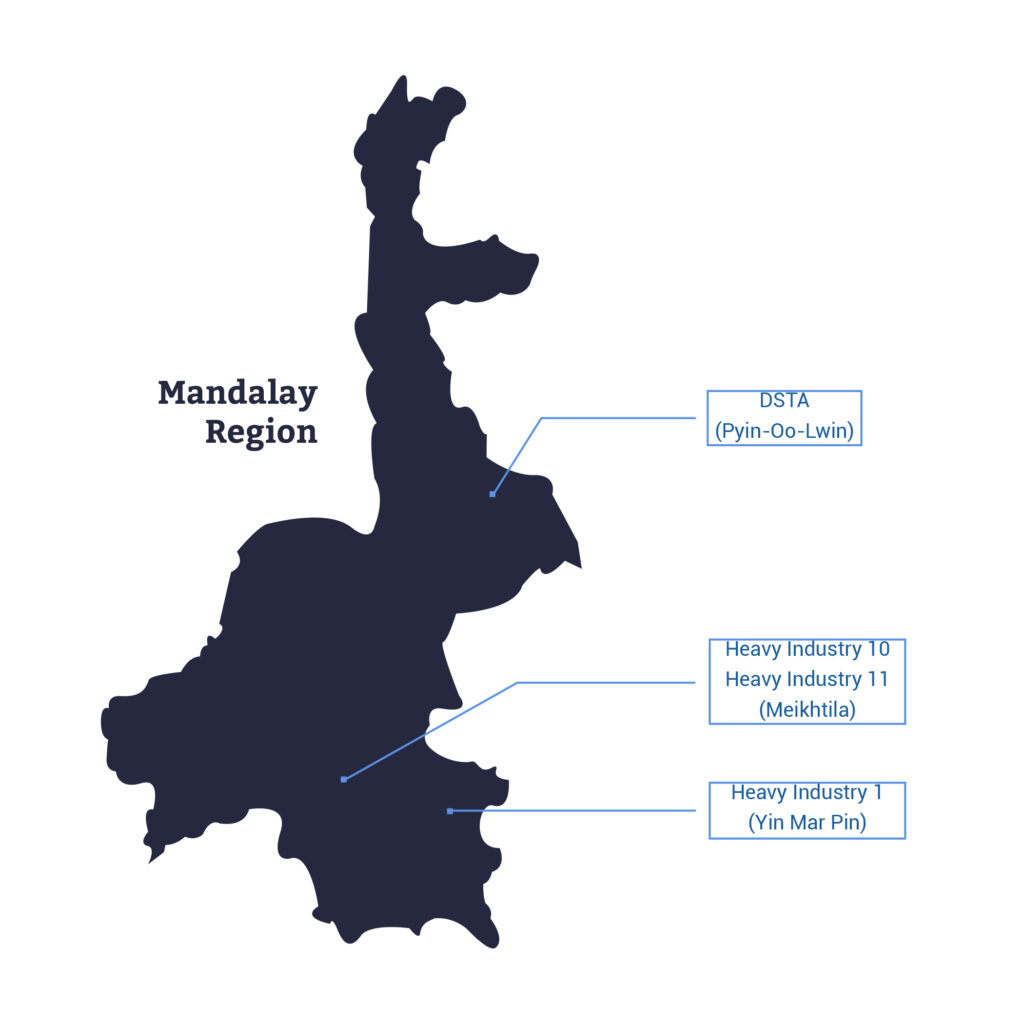

The supervision of production in each factory is done by officers from the Defence Service Technology Academy (DSTA, Pyin Oo Lwin, Mandalay Region). DSTA officers supervise a work force ranging from 1000 in the smaller factories to 3000 in the larger establishments. Among the 25 factories, KaPaSa 4, located in Tat Kone Township in Nay Pyi Taw, has been singled out as being particularly important for its role as a research centre, its in-house professional expertise in installing CNC machines and producing tool holders for CNC machines in use at other KaPaSa factories, and its support for the design of weapon production lines broadly.

The effective functioning of the KaPaSa factories is supported by central storage units for imported materials, parts and components, end items and machinery (KaHtaPa, commonly also referred to as “the store,” in Yangon), the Defence Materials Production School (KaHtaKa, located in Pyin Oo Lwin, Mandalay Region) and a Training School for KaPaSa factory workers (situated in Okeshitpin, Pandaung Township, Bago Region, in the vicinity of several KaPaSa factories). Three so-called “heavy industries” (TaKaSa) factories are also integral to the in-country manufacturing of products for military end-use: Heavy Industry Number 1 (manufacturing and assembling vehicles for the army), Heavy Industry Number 10 (producing components for aircrafts, drones and unmanned aerial vehicles) and Heavy Industry Number 11 (making components for, and assembling, armoured cars and light tanks), all three situated near Meiktila, Mandalay Region.

Beyond the network of KaPaSa factories and supporting institutions, the Myanmar armed forces also run other major military manufacturing sites, such as shipyards in Yangon, where naval frigates and corvette naval vessels are built, and military research and development institutes. There have also been longstanding rumours that some of the KaPaSa factories may be involved in developing a long-range ballistic missile program with technical expertise from North Korea.44 According to US national intelligence reporting, the Myanmar military also established a chemical weapons facility in Tonbo, Bago Region in the 1980s for the production of sulphur mustard;45 geo-localisation46 done in late 2020 suggests that this facility remains intact although it is not known whether this facility still holds any stocks.

The fact that the first KaPaSa factories were established in the late 1950s and that the military continues to refer to them as “Defence Industry” facilities is closely associated with the doctrine of the “people’s war” – developed in the 1960s by then military dictator General Ne Win – which emphasised the vital role of Myanmar’s armed forces to combat both domestic insurgents and to fend off the potential incursion of foreign armies. Under this doctrine, the military sees a central role for itself not only in the country’s earlier struggles for independence from the British, but also in “saving” the country from a wide range of external and internal threats.47 The latter has included groups opposed to centralised, military rule but also the military’s civilian critics and democracy activists from a wide range of ethnic groups, often referred to as “anarchistic mobs,” “destructionists” and “terrorists” by the military and its supporters in their propaganda.48 The ability to produce weapons in-country remains an important source of pride for Myanmar’s armed forces and is considered essential by its members and supporters in light of the perceived threats to the country’s unity and stability. The military has doubled down on this narrative after the 2021 attempted coup which has been met with widespread civilian resistance in the form of peaceful protests and the emergence of the civil disobedience movement (CDM). Local armed resistance groups, including People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), Local Defence Forces (LDFs) and People’s Defence Teams (PDTs), have also emerged in response to the military’s use of violence and lethal tactics against the population. The CDM and PDFs are now routinely referred to by the military as terrorist insurgents.

Numbers and Locations

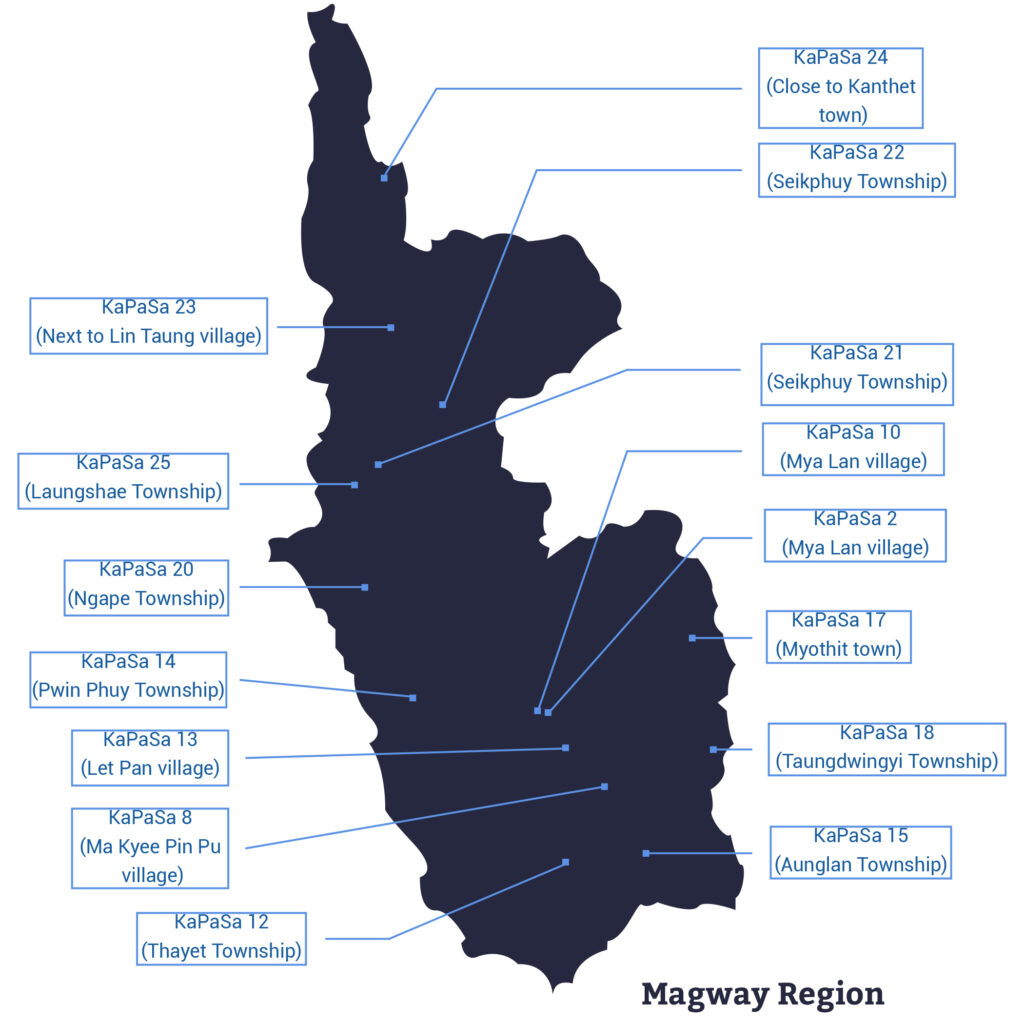

The DDI does not disclose the precise number of KaPaSa factories. Non-official estimates, however, suggest that the number of factories has multiplied from less than six prior to 1988 to “more than 20” in 201149 and to as many as 25 in 2022. Indicative of the order in which they have been established, the factories are commonly referred to as Defence Industry (DI) or KaPaSa followed by a number ranging from 1 to 25 (for example, DI-1 or KaPaSa 1). Two of the KaPaSa factories (numbers 23 and 25) are reportedly still in their construction phase and are not yet fully operational.50 According to information received by SAC-M, the production at these factories will potentially focus on strategic raw materials (KaPaSa 25) and chemicals (KaPaSa 23) to further reduce the military’s dependency on external supplies.

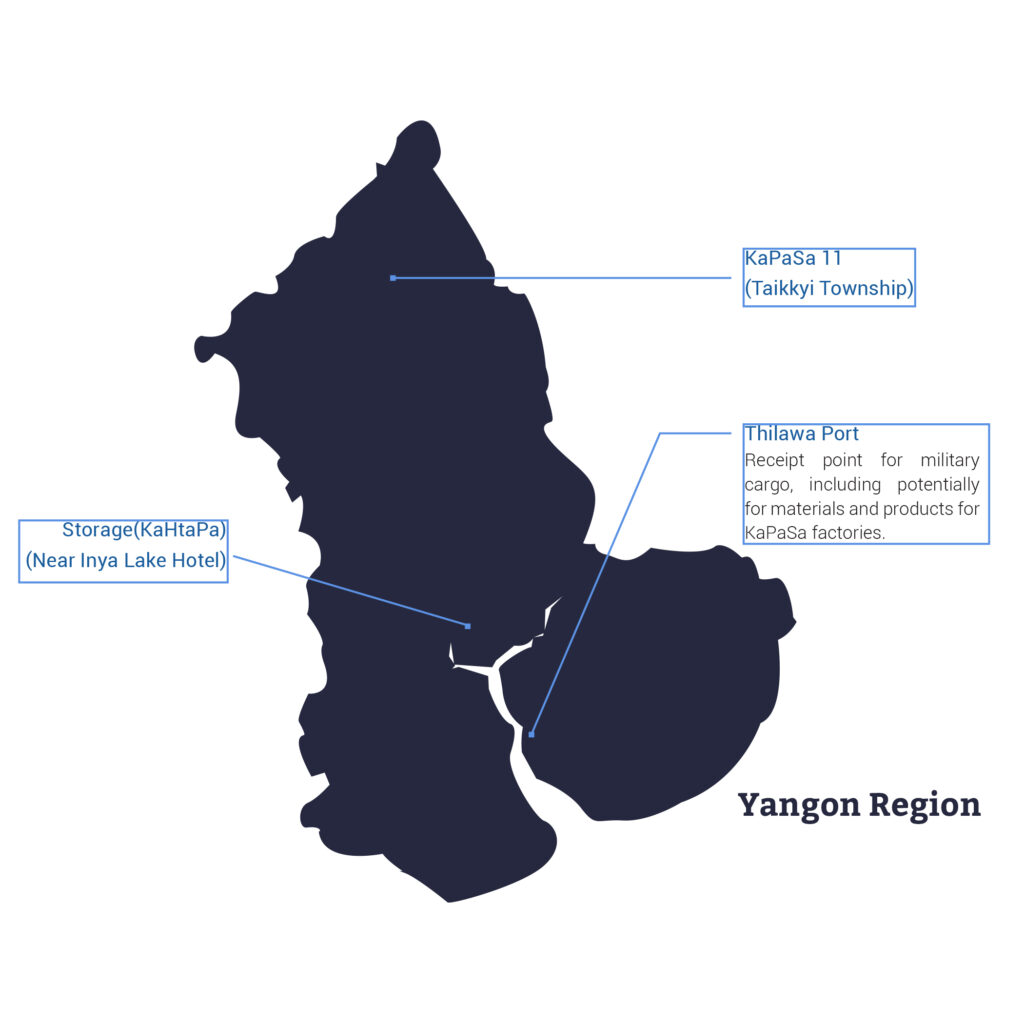

Historically, the early factories were located almost exclusively in and around the former capital Yangon on the western bank of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Pyay (formerly known as Prome) in the Bago Region, and in Magway Region further to the north.51 At present, the majority of the factories are located in Magway and, to a lesser extent, Bago, in the central part of the country. There are several reasons why the factories have been concentrated in these two regions:

- the central part of the country (Magway, Bago) has historically been under the military’s firm control and domination;

- Magway and Bago are remote and fairly sparsely populated and the population is predominantly Bamar Buddhist; this has, until recently, meant that the security of the facilities can be better guaranteed;

- many of the factories have specifically been built along the western bank of the Irrawaddy River as the river provides an important transportation route for the raw materials, parts and components, items and equipment needed for the production of weapons, and for the transport of ready-made products, such as ammunition, to various military units.

Wherever their location, the KaPaSa factories are well-connected to roads, ports, airports and rivers to facilitate the transport and inflow of necessary materials for sustained weapon production. By way of example, the Bassein-Monywa Highway is an important connecting point for, and supports the functioning of, several KaPaSa factories, while the Irrawaddy River has allowed the military to use barges52 to transport materials rather than having to rely on often inadequate roads.

To some extent, information about the locations of some of the factories is readily available in the public domain.53 While the military has not publicly disclosed the locations, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MOEE) listed, seemingly mistakenly, some of them in the context of its public disclosure of electricity stations in the Magway and Bago regions. The listed locations of KaPaSa factories in Magway were later removed in November 2021 from the military-run MOEE’s website.54 In addition, since the 2021 attempted military coup, more information about the factories has surfaced in both print55 and social media, providing additional indications about their locations, production lines and the transportation routes used by the military for supply. This increase in public information stems, in part, from the fact that the presumed factory sites appear to have been subject to sustained fighting between local resistance groups, including local units of PDFs, and the military.56 Such attacks, coupled with a reported increase in numbers of soldiers defecting from the KaPaSa factories,57 appears to be cause for significant concern for the military58 as illustrated by recent high-level visits from Nay Pyi Taw to KaPaSa facilities59 and retaliatory attacks by the military on civilians in Magway Region where the junta seemingly fears losing its stronghold.

Image: Maps showing the location of KaPaSa factories, central storage units (KaHtaPa) and other locations of strategic importance to KaPaSa production. This map prepared by SAC-M complements previous geo-localisation work done on the locations of KaPaSa factories.60

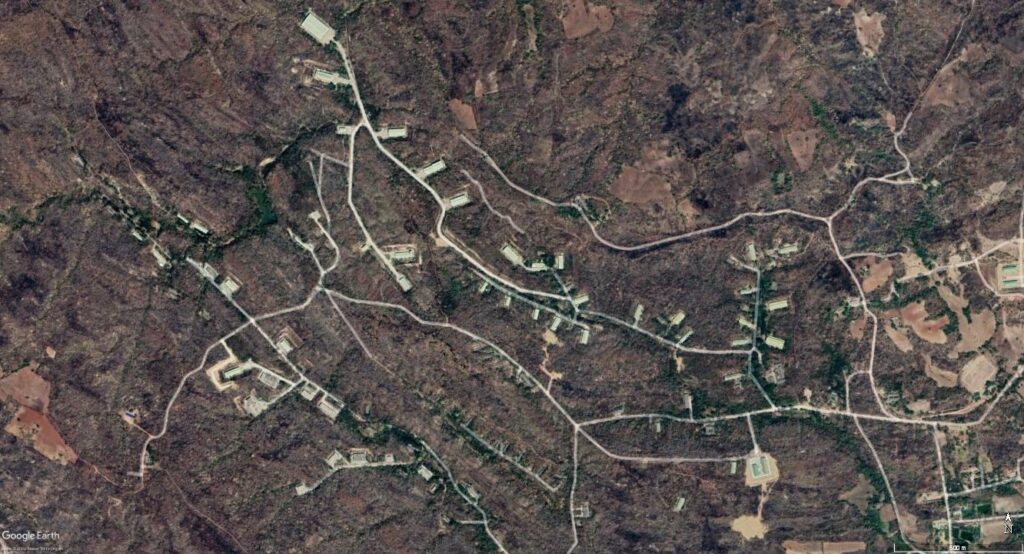

In-depth analysis of satellite imagery of a select number of KaPaSa facilities was done by the James Martin Center for Non-Proliferation Studies (CNS) in 2017 in response to concerns over a potential covert nuclear weapons programme in Myanmar. The CNS identified five factories in Magway Region, each of which presented “similar configurations, consisting of abnormally large square buildings, security perimeters, helipads, and barracks.”61 Specifically, the expert analysis indicates that:

“The sites all have security fencing (in some areas double perimeter fencing) and security gates on roads leading to the facilities, indicating the facilities are of value. The facilities are all located in remote areas away from population centers. In particular, the facilities are nestled in a long valley which provides them with natural cover. New paved roads lead to the facilities. This type of infrastructure is not typical in the area where the facilities are located, again indicating that the facilities are valued. Additionally, re-viewing historical imagery of the locations shows that this region is prone to flooding—the presence of paved roads indicates that access to these facilities is a priority. All of the facilities have a helipad on site, again indicating that the facilities are of importance and that high-level officials visit them. The facilities have housing units, both for individuals in charge of operations and visitors, and for the workers at the facilities. Large warehouses of an almost identical design are present at all the facilities… All of the facilities appear to play some role in manufacturing processes for the military organization that oversees them. There are slightly different features at the sites, indicating that they may be producing different items or are responsible for different pieces of a value chain.”62

While CNS only considered five (of the total 25) KaPaSa factories, SAC-M’s analysis of satellite images of the remaining 20 factories suggest similar design choices: they are located relatively far away from main settlements, consist of factory halls resembling hangars and have both administrative buildings and dormitories for on-site workers and their families.63 Some of the factory sites are very large in size, with the largest estimated at over 6000 hectares (15,000 acres), stretching for over 10 kilometres.

Helipads visible at KaPaSa 24

KaPaSa 22. This factory reportedly produces MA-1, MA-2, MA-3 and MA-4 small arms (mark III).

KaPaSa 10 that reportedly produces multiple launch rocket systems for vehicles.

Chinese State-owned company NORINCO appears to be playing an important role for the DDI’s imports of raw materials for KaPaSa production.

Production Lines

While the military in Myanmar has always been able to find countries willing to sell it arms – even after the imposition of arms embargoes and other restrictive measures imposed by many countries in 1988 – it has never been comfortable relying on foreigners for essential military supplies.64 Consequently, the DDI has prioritised developing its in-country capacity to manufacture such essential supplies.

Based on information shared with SAC-M by credible sources,65 current KaPaSa production lines include:

- Small arms66 including:

- assault rifles

- sniper rifles

- anti-material rifles

- light machine guns

- sub-machine guns

- general purpose machine guns

- a relatively recent indigenous copy of a 9×19 mm Glock handgun.

- Light weapons67 such as:

- heavy machine guns

- light and medium mortars, including 60 mm and 81 mm commando mortars

- anti-tank weapons, including rocket-propelled grenade launchers and recoilless rifles

- anti-aircraft guns, including 14.5 mm (QJG-02G) and 35 mm (MAA-01) guns, 25 mm self-propelled twin anti-aircraft guns, and type-91 14.5 mm quad guns

- various kinds of remote-controlled weapon stations68 for armoured vehicles and for sea-based combat platforms.

- Large calibre artillery systems69 including:

- towed artillery: 105 mm howitzer and 122 mm self-propelled howitzer (2-SIU)

- heavy mortars: 120 mm commando mortars and 120 mm extended range mortars

- multiple launch rocket systems: 122 mm rocket artillery and 124 mm rocket artillery systems.

- Air defence systems70 including:

- short-range man portable air defence system (SA-16)

- self-propelled short-range air defence system (MADV)

- medium-range air defence system (KS-1M).

- Missiles and missile launchers71 including:

- Man-Portable Air-Defence-Systems (MANPADs), including the short-range Igla-1E

(SA-16 Gimlet) - a variety of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), including short- and medium-range (KS-1)

and long-range (SA-5) - short-range tactical ballistic missiles (Hwasong-5) in collaboration with the Democratic

People’s Republic of Korea.72

- Man-Portable Air-Defence-Systems (MANPADs), including the short-range Igla-1E

- Ammunition and associated components73 such as:

- small arms ammunition (including 5.56×45 mm NATO, 7.62×51 mm NATO, 9×19 mm

parabellum) - anti-aircraft gun ammunition (12.7×108 mm, 14.5×114 mm)

- grenades including hand grenades,40 mm rifle grenades and 40mm launcher grenades, 73 mm and 75 mm anti-personnel rocket propelled grenades

- 57 mm, 77 mm and 122 mm rockets

- 60 mm, 81 mm and 120 mm mortar bombs

- 76 mm, 105 mm, 122 mm, 130 mm and 155 mm ammunition for towed guns

- 122 mm and 240 mm rockets

- 50 kg/100 kg/200 kg/250 kg/500 kg unguided bombs for the air-force

- FT-2 precision-guided bombs (500 kg)

- aerosol bombs and a variety of ammunition for the navy (12.7/14.5/25/37/40/57/75 mm)

- a variety of anti-personnel and anti-vehicle landmines

- naval mines

- cluster munition

- AZDM 111 A 1/2 fuses

- explosives, including TNT74 and RDX,75 emulsion explosives and other high explosives.

- small arms ammunition (including 5.56×45 mm NATO, 7.62×51 mm NATO, 9×19 mm

- Weapon sites including optical sights for 40 mm and 60 mm rocket launchers as well as sights for 81/120 mm mortars.

The DDI also produces various tanks, armoured vehicles and utility vehicles, with new types of vehicles seen to enter production following a 2019 agreement between the DDI, military crony company Myanmar Chemical & Machinery, the Ukrainian State-owned arms conglomerate Ukronoronprom and State-owned arms trading company Ukrspecexport.76 Under the supervision of the DDI, military uniforms and accessories, including uniforms, shoes, bullet-proof vests and magazine pouches are also produced in country. Lastly, at one of its Heavy Industries in Meiktila, Mandalay Region, the military also reportedly produces unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

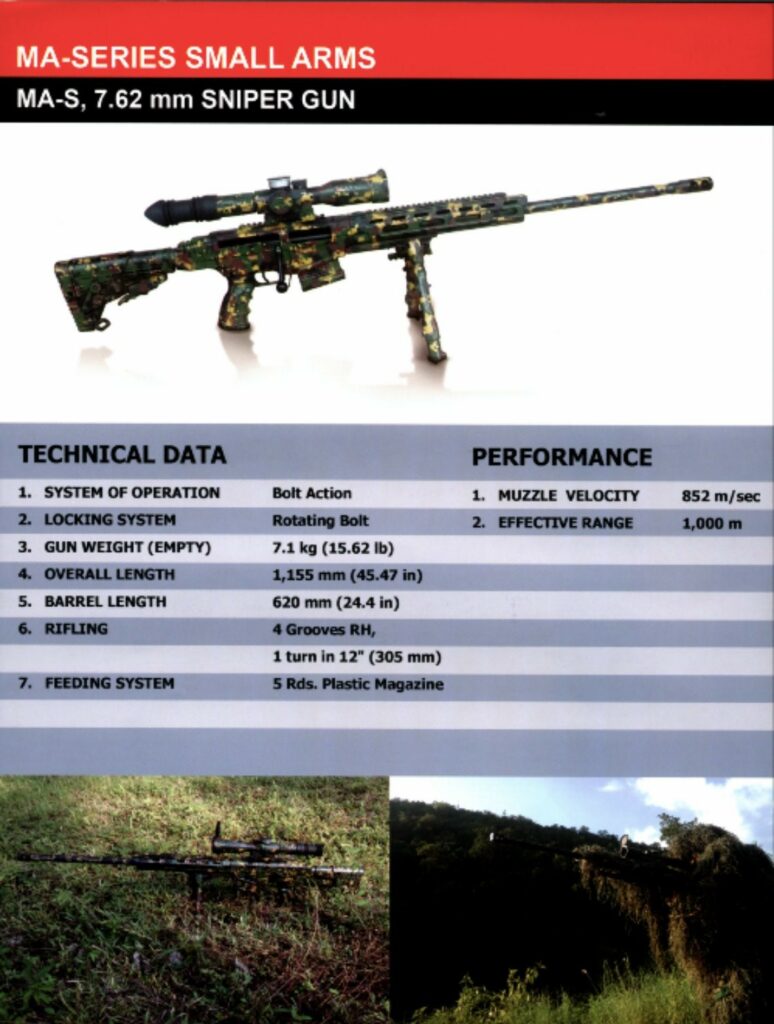

At present, there is no information to suggest that the DDI exports its weapons to other countries. Nevertheless, the fact that the military, for the first time, showcased its products at the Defense & Security 2019 show in Thailand may attest to the military’s intention to do so in the future.77 Commenting on this participation, a representative of the military’s delegation noted the DDI’s interest to seek to enter foreign markets, in particular in the Southeast Asia region, potentially focusing on exporting the made-in-Myanmar sniper-rifle (MA-S).78

A flyer for the Myanmar-made sniper rifle (MA-S) as showcased by the DDI at the Defense & Security 2019 expo in Thailand.

The DDI’s stand at the Defense & Security 2019 expo in Thailand, showcasing a variety of weapons made in Myanmar.

Cartridges for various firearms, as showcased by the DDI during the Defense & Security 2019 expo in Thailand.

Grenades, bore cartridges and fuses manufactured at KaPaSa factories and showcased at the Defense & Security 2019 expo in Thailand.

Locally produced mortars, as showcased at the Defense & Security 2019 expo in Thailand.

Cannon ammunition produced at KaPaSa factories and displayed at the Defense & Security 2019 expo in Thailand.

A Myanmar-made rocket propelled grenade launcher (RPG) and Myanmar-made rocket propelled grenades showcased at the Defense & Security 2019 expo in Thailand.

Captured DDI manufactured landmines. In December 2019, seven MM-2 landmines planted by the Myanmar army were discovered near Wan Wah village of Murng Mu Region in Namtu Township, northern Shan State. Photograph originally published on Facebook by the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) on 3 December 2019.

While there are some publicly available estimates about the quantities of the specific categories of weapons that the DDI produces on an annual basis, its actual production capacity is opaque. Complicating the matter further is the fact that a number of rumours and misconceptions about Myanmar’s armed forces persist, with some portraying the military as an “enormous, well- resourced and efficient military machine” and others characterising it as “a hollow shell, lacking committed personnel and professional skills, riven by internal tensions and preoccupied with the crude maintenance of political power.”79 Consequently, any available figures about the DDI’s arms production outputs should be considered indicative at best.

The DDI uses the designation of “MA” for Myanmar Army (or alternatively M, for Myanmar) for the nomenclature of most of the made-in-Myanmar weapons.80 Over the years, the weapons have been constantly upgraded and improved as a means to respond to reports of malfunctioning and to increase accuracy. To designate these upgrades, the DDI has added an “MK”-suffix followed by the number of the variation (mark I, II, III) to its nomenclature.

DDI-made weapons come with their unique marking – the triangle crest.81 Where the triangle crest is missing, there may be other ways to distinguish DDI-made products. In the case of tail booms of mortars, the colour, stencilling or other serial number markings may be indicative of their manufacture in Myanmar. According to information received by SAC-M, recent markings imprinted on DDI-made mortar projectiles include markings ER (most likely standing for explosive round), coupled by a number indicating year of manufacture (such as 21 for 2021) and a number confirming batch (such as 318).82

The ability to produce weapons in-country remains an important source of pride for Myanmar’s armed forces and is considered essential by its members and supporters in light of the perceived threats to the country’s unity and stability.

Ammunition reportedly used in North Okkalapa Township, Yangon, on 3 March 2021 in response to protests include, second and third from the top, 5.56 mm and 9 mm rounds both carrying the headstamp of the Directorate of Defence Industry and manufactured in Myanmar.

The headstamp on a 5.56 × 45 mm cartridge produced by DDI. The year of production (2010) and calibre (5.56) are marked in Burmese numerals and the headstamp also incorporates the DDI triangle crest.

Photo by Miles Vining via: https://armamentresearch.com/the-yat-thai-rifles-of-shan-state-myanmar/

A protester shows a cartridge during a protest in Mandalay against the attempted military coup. Note the DDI’s triangle crest on the primer annulus, confirming local manufacture.

Footnotes:

33 The State-owned Economic Enterprises Law (the State Law and Order Restoration Council Law No.9/89) defines 12 economic activities in which private investment is restricted and reserved to be carried out solely by the government. These activities include the “manufacture of products relating to security and defence which the Government has, from time to time, prescribed by notification” (Section 3, l.). In 2017, the Myanmar Investment Commission also issued a list of restricted investment activities including the “manufacturing of products for security and defence…” and the “manufacturing and related services of arms and ammunition for the national defence.” See Myanmar Investment Commission “Notification No. 15 /2017: List of Restricted Investment Activities.” Available at: https://www.myanmartradeportal.gov.mm/legal/133 (Accessed 14 January 2023).

34 The DDI is also commonly referred to as the Ministry of Defence Directorate of Defence Industries, the Myanma Defence Product Industry, or simply the Defence Product Industries and is located in Nay Pyi Taw.

35 There is some level of disagreement between informants about who oversees the DDI. As regards the organisation and control of the KaPaSa weapon manufacturing complex, there is most likely a formal, conventional structure (with the DDI being part of the Ministry of Defence), but at the same time with the Director of Procurement reporting directly to the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces. The higher levels of Myanmar’s armed forces often reach down into the wider defence organisation to oversee or manage key issues, including the acquisition of new weapons and the development of new capabilities. There also seems to be considerable overlap between the responsibilities of the Ministry of Defence and Myanmar’s military itself.

36 Interview with #J2, 8 April 2022, and confirmed also by the publicly available list of participants in the Myanmar delegation to the 2019 Defence and Security exposition in Thailand at which the DDI showcased, for the first time, its Myanmar-made weapons.

37 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 2022, Military Expenditure Database: 2021

38 See Selth, A., 2016, ‘“Strong, Fully Efficient and Modern”: Myanmar’s new look armed forces,’ Griffith’s Asia Institute Regional Outlook Paper No. 49, pg. 6. Available at: https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/118313/Regional-Outlook-Paper-49-Selth-web.pdf (Accessed 10 January 2023).

39 “Myanmar Military Files Show Systemic Corruption and Implicate International Businesses,” Justice for Myanmar, 8 December 2020. Available at: https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/stories/myanmar-military-budget-and-procurement-files (Accessed 10 January 2023).

40 For example, different KaPaSa factories produce a specific generation of the MA-series of small arms (mark I, mark II, mark III).

41 Tool holders are one of the main parts of CNC machines, connecting the machine tool with the tooling. They play an imperative role in the correct and precise manufacturing of weapon systems.

42 Interview with #V4, 2 August 2022.

43 Dual-use technologies refer to goods, software and technology that can be used for both civilian and military applications. These can be acquired by the Myanmar armed forces and adapted, at KaPaSa facilities, to suit their own purposes. There have been reports, for example, that Australian-manufactured radios were purchased and modified by the Myanmar armed forces before being operated in the field. See, for example, Ball, D., “‘How the Tatmadaw Talks: The Burmese Army’s Radio Systems’ Working Paper No. 388,” Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 2004. Avalaible at: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/86757 (Accessed 10 January 2023).

44 Xu, T., “Institutions Relevant to Ballistic Missile Development in Myanmar,” The Open Nuclear Network, 26 November 2021. Available at: https://opennuclear.org/publication/institutions-relevant-ballistic-missile-development-myanmar (Accessed 10 January 2023). See also Lintner, B., “Myanmar-North Korea on a new missile making mission,” Asia Times, 23 March 2022. Available at: https://asiatimes.com/2022/03/myanmar-north-korea-on-a-new-missile-making-mission/ (Accessed 10 January 2023).

45 Koblentz, G., and Roty, M., “Myanmar should finally come clean about its chemical weapons past—with US help,” Bulleton of the Atomic Scientists, 11 March 2020. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/2020/03/myanmar-should-finally-come-clean-about-its-chemical-weapons-past-with-us-help/ (Accessed 10 January 2023).

46 Geo-localisation refers to the process of identifying the exact location of one or several sites based on information derived from an analysis of data and/or images associated with a particular location.

47 In terms of weapon production at KaPaSa factories, this dual role of defending the country against both external and internal threats is seen in some of the DDI’s choices for production lines: for example, the DDI can produce, in country, a 12.7 mm heavy machine gun which can be used against slow and low flying aircraft, such as helicopters, but in the Myanmar context this type of weapon is unlikely to be of use as none of the groups currently opposing the junta and fighting it have helicopters.

48 Mathieson, D.S., “Glaring glimpse into Myanmar military’s self-delusion,” Asia Times, 29 April 2021, as quoted by Selth, A., 2021: “Myanmar’s military mindset: An exploratory survey,” Griffith University. Available at: https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/1418333/Military-mindset-web.pdf (Accessed 10 January 2023).

49 Lintner, B., “Toys for the boys in Myanmar,” Asia Times, 6 September 2011. Available at: http://peacefulburma.blogspot.com/2011_09_09_archive.html (Accessed 10 January 2023).

50 Interview with #V4, #V20 and #V11, 30 July 2022.

51 Lintner, B., “Toys for the boys in Myanmar,” Asia Times, 6 September 2011.

52 A barge is a type of marine vessel that is mainly used for cargo transportation. Barges are typically used in lakes, canals, and inland waterways, and often at seaports.

53 For example, Viettel Construction inadvertently released information about four KaPaSa factories in Magway in connection with the establishment of Mytel towers inside the factories. See also, Lintner, B., “Burma’s WMD Programme and Military Cooperation between Burma and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” Asia Pacific Media Services, 2012, which lists, in an annex, the location, size, workforce and production lines of 20 KaPaSa factories. Based on more recent reporting on production lines at each KaPaSa factory this list now appears to be largely out of date.

54 Specifically, prior to 17 November 2021, the MOEE’s overview of the grid in Magway Region also listed ten factories; since then, under the now junta-controlled ministry, this information has been removed from the site.

55 For example, in July 2022, the Burmese edition of Myanmar Now made public a map with all the KaPaSa factory sites and an overview of each factory’s production lines, reportedly based on interviews with CDM soldiers. Available at: https://m.facebook.com/myanmarnownews/photos/a.545566185591124/2478585905622466/ (Accessed 14 January 2023).

56 Since 2021, military convoys travelling to or from KaPaSa factories have been subject to targeted attacks (see, for example, Min Min and Nyein Swe, “Resistance forces seize materials to build weapons, military responds with airstrikes,” Myanmar Now, 8 April 2022. Available at: https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/resistance-forces-seize-materials-to-build-weapons-military-responds-with-airstrikes Accessed 10 January 2023)) and attempts have been made to disrupt production (for example, in December 2021, local PDFs carried out attacks on an electricity tower supplying six KaPaSa factories).

57 Interview with #J2, 7 May 2022. See also: Zaw Ye Thwe and Min Min, “From Battlefields to Hospitals, short-staffed junta moves personnel into vacant roles,” Myanmar Now, 26 April 2022. Available at: https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/resistance-forces-seize-materials-to-build-weapons-military-responds-with-airstrikes (Accessed 10 January 2023).

58 See, for example, “Armed resistance replaces anti-coup protests in Pauk Township,” Frontier Myanmar, 31 August 2021, which states that “control of the region is particularly important for the Tatmadaw, because it is home to a Directorate of Defence Industry that produces military supplies like firearms and grenades for the security forces.” Available at: https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/armed-resistance-replaces-anti-coup-protests-in-pauk-township/ (Accessed 10 January 2023).

59 Interview with #J2, 7 May 2022.

60 Hintz, F., 25 December 2020: https://twitter.com/fab_hinz/status/1342250468198776832. See also map published by Myanmar Now (Burmese edition), 2 August 2022.

61 Hanham, M., Dill, C., Lewis, J., Bo Kim, Schmerler, D., and Rodgers, J., June 2017, “Occasional Paper n. 28: Geo4nonpro.org: A Geospatial Crowd-Sourcing Platform for WMD Verification,” James Martin Center for Non-proliferation Studies. Available at: https://nonproliferation.org/op28-geo4nonpro-org-a-geospatial-crowd-sourcing-platform-for-wmd-verification/ (Accessed 10 January 2023).

62 Hanham, M., Dill, C., Lewis, J., Bo Kim, Schmerler, D., and Rodgers, J., June 2017, “Occasional Paper n. 28: Geo4nonpro.org: A Geospatial Crowd-Sourcing Platform for WMD Verification,” James Martin Center for Non-proliferation Studies, pg. 25, references omitted.

63 According to information shared with the SAC-M, KaPaSa factory workers live on site with their families; some of the more recent factories can house up to 1500 workers and approximately the same number of family members.

64 Selth A., 2000, “Landmines in Burma – the Military Dimension,” Canberra Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. Available at: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/219659/1/WP-SDSC-352.pdf (Accessed 10 January 2023).

65 These sources include, among others, individuals with first-hand experience of the military’s weapon production; military-controlled media outlets, discussions on social media forums and closed messaging groups, and images of the Myanmar DDI’s booth at the Defense & Security 2019 expo in Thailand where the DDI showcased its products for the first time. The list has also been complemented based on interviews with experts on the design, production, and employment of various military platforms (air, naval, army) in Myanmar. It should be noted, however, that, because of the opacity of the DDI’s production and the fact that the sprawling network of KaPaSa factories and associated strategic facilities is constantly changing, this list may not be complete, and some of the items listed may no longer be in production.

66 Broadly speaking, small arms refer to weapons designed for individual use, such as revolvers and self-loading pistols, rifles and carbines, sub-machine guns, assault rifles, and light machine guns. See the International Tracing Instrument (ITI) within the framework of the UN small arms process.

67 Light weapons are, broadly speaking, weapons designed for use by two or three persons serving as a crew, although some may be carried and used by a single person. They include, inter alia, heavy machine guns, hand-held under-barrel and mounted grenade launchers, portable anti-aircraft guns, portable anti-tank guns, recoilless rifles, portable launchers of anti-tank missile and rocket systems, portable launchers of anti-aircraft missile systems, and mortars of a calibre of less than 100 millimetres. See the International Tracing Instrument (ITI) within the framework of the UN small arms process.

68 Remote controlled weapon stations refer to remotely operated weaponised systems often equipped with fire-control systems for light and medium-calibre weapons which can be installed on a ground combat vehicle or sea- and air-based combat platforms.

69 The United Nations Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) defines large calibre artillery systems as guns, howitzers, artillery pieces, combining the characteristics of a gun or a howitzer, mortars or multiple-launch rocket systems, capable of engaging surface targets by delivering primarily indirect fire, with a caliber of 75 millimetres and above.

70 Air defence systems serve the purpose of protecting military bases, assets and mobile platforms from aerial threats such as combat aircraft, attack helicopters, unmanned air vehicles as well as incoming missiles, guided munition, and rockets.

71 The United Nations Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) defines missiles and missile launchers as guided or unguided rockets, ballistic or cruise missiles capable of delivering a warhead or weapon of destruction to a range of at least 25 kilometres and means designed or modified specifically for launching such missiles or rockets.

72 See, for example, Xu, T., November 2021, for the Open Nuclear Network ‘Institutions Relevant to Ballistic Missile Development in Myanmar.’ See also Lintner, B., 23 March 2022, Asia Times, ‘Myanmar-North Korea on a new missile making mission.’ It should be noted, however, that, while there has been a great deal of speculation about the type of assistance that North Korea has provided or helped the Myanmar armed forces manufacture, few hard facts have emerged. There have been no confirmed sightings, for example, of a Hwasong-5 in Myanmar.

73 Ammunition refers to the material that is fired, scattered, dropped or detonated from any weapon or any weapon system. The term includes both expendable weapons (such as bombs, missiles, grenades, and landmines) and the component parts of other weapons that create the effect on a target (such as projectiles, bullets and warheads).

74 Trinitrotoluene, a common type of military explosive.

75 RDX is a nitramine explosive compound that can be utilised as a propellant, gunpowder, or high explosive.

76 “Ukraine is arming the Myanmar Military,” Justice for Myanmar, 8 September 2021. Available at: https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/stories/ukraine-is-arming-the-myanmar-military (Accessed 10 January 2023). Ukrspetsexport has confirmed an initial delivery of equipment and machinery for the plant which was scheduled to commence production by 2020. See also, Malyasov, D., “Ukraine to build armoured vehicle assembly plant in Myanmar,” Defence Blog, 6 March 2019. Available at: https://defence-blog.com/ukraine-to-build-armoured-vehicle-assembly-plant-in-myanmar/ (Accessed 10 January 2023).

77 The products presented by the DDI at the Defense & Security 2019 expo included mortars, grenade launchers, machine guns, rifles, other small arms, scopes and ammunition of large and small calibre.

78 Based on information in media article shared during interview with #J2, 8 May 2022.

79 See Selth, A., 2016, ‘Strong, Fully Efficient and Modern’: Myanmar’s new look armed forces (Griffith’s Asia Institute Regional Outlook Paper No. 49) pg. 6, footnotes omitted.

80 Prior to adopting this nomenclature in the late 1990s, older models were labelled “BA” for Burma Army. For the most part, the model numbers associated with the BA nomenclature corresponded to the year they were adopted (e.g., the BA-63, adopted in 1963). See Vining, M., “The Burmese BA-93, A Modified Lee Enfield Rifle Grenade Launcher,” The Firearm Blog, 11 August 2018. Available at: https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2018/11/08/the-burmese-ba-93-a-modified-lee-enfield-rifle-grenade-launcher/ (Accessed 10 January 2023). Anti-personnel and anti-vehicle landmines that are locally manufactured and are typically referred to as MM (Myanmar mine) followed by a number to indicate the precise model.

81 In the case of older mortar projectiles, the colour and stencilling may also provide indication that they have been manufactured in Myanmar.

82 Vining, M., “The MA-13 MK II: Myanmar’s Steyr/Micro Uzi Knock-off,” The Firearms Blog, 20 July 2018. Available at: https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2018/07/20/the-ma-13-mk-ii-myanmars-steyr-micro-uzi-knock-off/ (Accessed 10 January 2023).